What should the Christian churches do to address the way in which religion has become politicised in the context of the Northern Ireland conflict?

Let me approach this in two ways by asking, first, what Scripture implies they should do, and secondly, asking what they can actually do within the constraints of Northern Ireland’s politics?

First, then, what is the message of Christianity for the churches? The Bible begins with two accounts of creation narrated in Genesis 1–3 and closes with an account of new creation. The basic catechism of the Roman Catholic, Orthodox and mainline Protestant churches begins with the creation of the world by God marred by the fall of the first parents and revived by the New Adam (Jesus Christ) through his passion, death and resurrection.

Salvation is an important concept in Christianity. The God of Christianity is a provident God who progressively through linear time feeds, heals, protects and, above all, forgives; forgives to the point eventually of his son dying on the cross to redeem people’s sins.

Numerous texts in the Old Testament speak of God’s forgiveness. There is an emphasis on good deeds which produce goodness for thousands of generations, and on evil deeds carrying evil to the third and fourth generation. In other words, evil creates a culture of evil, but such is short lived in comparison to the effects of goodness which are almost eternal.

This is expressed in the New Testament by Paul in different words saying ‘Love is eternal’. (Corinthians 13, 13). The New Testament is a charter of forgiveness because of the iconic symbol of Jesus. The meal tradition of the New Testament (for example, Luke 5,27–39; 7,36–50; 19,1–10) and the parable of the prodigal son (Luke 15,11–32), are symbolic of Jesus’ forgiving mission. The importance of human beings forgiving one another is also reiterated in the Bible. ‘And if the same person sins against you seven times a day, and turns back to you seven times and says, “I repent”, you must forgive.’ (Luke 17, 4). According to the Lord’s Prayer, forgiving one’s fellow human being is a condition to be forgiven by God (Matthew 5, 12; Luke 11,4).

One of the issues dealt with in the prophetic literature of the Old Testament is the condemnation of violence (for example, Isaiah 5, 7; Jeremiah 6, 7; 22, 3; Ezekiel 28, 16 and Amos 3,10). Similarly, the New Testament also teaches non–violence (Matthew 5, 38–39, 44; Romans 12, 17–21; 1Peter 3, 9). Jesus stood against violence by responding non–violently. This led Jesus himself and his followers in the Early Church to see him as the suffering–servant who does not respond to violence with violence. The dictum of turning the other cheek is synonymous with Jesus’ calling. The Christian life is a calling to selfless forgiveness.

Given this Christian injunction, the key issue becomes what is feasible in Northern Ireland, where religion and politics elide and religion is corrupted. To answer that I want to return to the six problems of Northern Irish religion raised at the beginning, and to close by coming full circle. I suggest the Churches should:

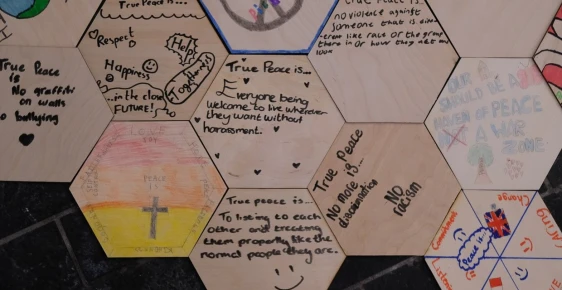

Address hermeneutical issues and use doctrine to undergird peace by retrieving the excised parts of doctrine that encourage empathy toward neighbour, stranger and the erstwhile enemy, and to prioritise texts that promote love, respect, tolerance, forgiveness, grace and mercy.

Depoliticise religion. Own up to their culpability in the past, their own sins of omission and commission, and acknowledge their contribution to the perpetuation of division. The churches’ ‘charitable hatred’ as religious enmity in the past has been called, needs to be acknowledged.

Uncouple the practice of religious faith from the practice of cultural religion. Faith commitments need to be separated from the formation of ethno–national identity, such that the churches should preach loyalty to Jesus Christ not Ulster or Mother Ireland as believers’ principle identity.

The churches should show unity around the key Christian principles of forgiveness, mercy, compassion, empathy, grace and justice, principles that define Jesus’ new covenant rather than fragment. These canonical precepts are sorely needed as people emerging out of conflict try to learn to live together in tolerance.

Inter–denominational and inter–religious respect between faith–based organisations and communities should model the culture of tolerance, respect and compassion that the churches aspire to realise in society generally, making religion truly non–partisan.

The churches should develop a public role in which they become part of the solution in dealing with the legacy issues of the conflict. This means not hiding behind a veil of personal piety but entering the public square and contributing to public debate.

Let me say finally that I realise this is a hard calling in the context of the legacy of Northern Ireland’s conflict. Thus, the churches as institutions need to show bravery, courage and risk–taking and to lead post–conflict recovery from the front. In a recent article in The Irish Catholic Martin O’Brien said the Catholic Church lived in a bunker. All Northern churches exist as bunkers in two senses I think. They are physical bunkers, buildings divorced from the social problems surrounding them, especially the commuter churches from which the middle classes retreat back to the suburbs every Sunday. And they are mental silos, retreats into personal piety that shield people from the risks, anxieties and challenges of learning to live together in tolerance.

They need to be outward looking not inward, practising their faith in society not just within their walls. Like John’s Gospel urges, the churches themselves need to walk as Jesus walked in first–century Palestine; they have no better question to ask themselves than what Jesus would do now in Northern Ireland. And I read my Bible enough to know Jesus had a public ministry as a risk–taker for peace.