Being churches together: celebrating a reconciling vision of hope

by Allan LEONARD

7 September 2023

A “Being Churches together in 21st Century Ireland” symposium took place at Dublin City University (DCU), as part of a number of events marking the centenary of the Irish Council of Churches (ICC) and 50 years since the Ballymascanlon talks that led to the formation of the Irish Inter–Church Meeting (IICM).

Bishop Brendan Leahy (IICM Co–Chair) began with a prayer before putting this year’s anniversary events in the context of continuing a “celebration of our reconciling vision of hope”:

“We are in a new moment in Ireland. We have new challenges, common to all of us, which are very different to what was there 100 years ago. And we want to keep hope alive, as an important ingredient for our engagement with one another.”

Bishop Leahy continued with reference to French writer, Charles Péguy, with an image of three sisters whereby “faith” is a strong character, “love” represents compassion, and “hope” is more childlike and innocent:

“Faith and love, if they don’t have hope, they get de–energized. Hope is what ultimately keeps you going. Hope gives the energy… So, yes, the many challenges that face us may cause faith and love to diminish. Hope can rekindle.”

Three speakers were invited to address how churches could come together in Ireland, to bring their values to bear witness to polarising and fracturing pressures in society.

Professor Philip McDonagh (DCU) spoke on “Witnessing for a reason: connecting Christian values and public concerns”.

Prof. McDonagh’s career includes years of service in the Department of Foreign Affairs (Ireland), five of which were on the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement. Indeed, he referenced US Senator George Mitchell’s speech on the 25th anniversary of the agreement in introductory remarks:

“The Good Friday Agreement was not a mere ‘political fix’, as some people might say. Words like justice, peace, relationships, and reconciliation were the lingua franca of the time. As Senator George Mitchell stated in Belfast last April, ‘Peace is a true idea.’ But in that same speech, Senator Mitchell points out that ‘every one of us is fallible’, and ‘history is never finished’.

“So, we can hold two thoughts in our minds at the same time. On the one hand, as Senator Mitchell said, the Good Friday/Belfast Agreement ‘talks to the world’ in these ‘fractured times’. On the other hand, as Archbishop Eamon Martin said in St Anne’s Cathedral in January of this year, our agenda for the next 50 years as churches in society should be bigger and broader than our own peace process. Our coming together today to discuss wider challenges may even bring new life to the peace process itself.”

McDonagh argued that mercy and hope, like peace, are true ideas. He used Saint Paul’s letter to Philemon for this, whereby St Paul made it clear that the slave should only be returned to his master on the basis of an assurance that he will no longer be treated as a slave is usually treated. The dilemma is resolved through a deliberate act of mercy by the slave master. McDonagh argued that this act of mercy at a ‘micro’ level will have long–term consequences at the ‘macro’ level — that ultimately the institution of slavery cannot survive in an atmosphere of interpersonal communication and communion: “Today, even ‘micro’ decisions, if they are inspired by a sense of justice as a felt absence, anticipate a broader social change.”

There were three main points of McDonagh’s talk. First, the missing ingredient in our politics is methodological: “We often seem incapable of deliberation and discernment from a deep and long–term perspective, which is why the voice of the churches is so important.” Second was a description of three projects of engaged research undertaken by the Centre for Religion, Human Values, and International Relations at DCU over the past two years. Third was an offer of four suggestions for churches to consider.

On the first point, McDonagh cited French Roman Catholic bishops in making the case for placing different spheres of knowledge at the service of the common good: “A few years ago, [they] wrote about the need to ‘recover the meaning of politics’, making a distinction between le politique — understanding what a shared life in society involved — and la politique — the specific actions and policies that we debate in each electoral cycle.” McDonagh concluded that what is needed is to reconnect overarching values and practical policies by exploring in greater depth the relationship between them: “The voices of Christians, of other religious believers, and of all people of principle are indispensable if such a process is to bear fruit.”

One of McDonagh’s suggestions was to continue to explore spaces in which public authorities can deepen their dialogue with churches and faith communities. He elaborated on the further development of the Article 17 framework at the European Parliament, which provides such structured dialogue. (Earlier this year, Co–Chairs of the IICM, Bishop Andrew and Bishop Brendan, wrote to First Vice–President of the European Parliament, Dr Othmar Karas, who provided a positive response.)

Prof. McDonagh concluded with what he called “citizenship obligations in the kingdom”:

“Our baptism ought to lead to the appropriation of concrete citizenship obligations in the kingdom to which Jesus was the witness. St Paul, in Philippians, identifies a ‘deep–felt mercy’ as a principal characteristic of those who embrace the new form of shared life. The spirit of mercy draws us into a differently imagined social space. Well–trained judgement exercised in company with others enables us to deliberate about the future… and to move forward in hope.”

Dr Nicola Brady (Churches Together in Britain and Ireland) addressed “Witnessing together: how churches build connection and work together effectively”.

Dr Brady began her presentation by addressing the question, “What do we mean by building connection?” She suggested that it meant churches reaching out beyond themselves, to include wider civic society as well as government and policymakers. The rest of her presentation was a set of prompts for consideration.

For example, she asked, “What is the story we churches want to tell?”, with points on context, purpose, and process.

For context, on the one hand, some bad actors are not getting scrutinised. On the other hand, people do want to hear hopeful messages and stories of leadership, such as the new book by Ian Ellis, Called to be One, honouring the centenary of the ICC and 50th anniversary of the IICM. Brady suggested that this book could get all on the same page in a journey together, underlining positive outcomes over the decades of ICC and IICM work — an increase of trust amongst the churches, more joint projects, and more inquiries about the organisations’ works.

For purpose, Brady warned of a danger of developing a rich internal dialogue within the churches, without links to the outside world. She was calling for an engagement beyond the faith sector.

For process, Brady said that framing is essential, particularly with political engagements, where there needs to be mutual respect and the spirit of friendship as an underlying value: “Treat politicians as human beings.”

Rev. Dr Livingstone Thompson (Moravian Church) spoke on “Witnessing in diversity: churches working for an Ireland of belonging”.

Rev. Thompson began by remarking that 100 years ago, it was “a bold thing” in Ireland for the denominations of Catholics and Protestants to sit together. He said that now the ecumenical imperative has shifted to how churches deal with individuals in their congregations. That is, what does inclusion look like within congregations and wider society, he asked.

He presented statistics to illustrate some demographic changes over recent decades. For example, between mid–2000 and mid–2018, there was an estimated net total of 41,000 new residents from abroad in Northern Ireland (Table 1.1), as well as a marked increase in demand for its health services to provide language interpretation: “The question is not whether diversity is increasing, but the speed at which it is happening.”

This change is also reflected in an increase in racism in Ireland, north and south, citing Judge Desmond Marrinan’s independent review of hate crime legislation in Northern Ireland. In its evidence to the Northern Ireland Affairs Committee at the House of Commons, for example, the North West Migrants Forum stated that one is 17 times more likely to be a victim of a hate crime in Northern Ireland than of a sectarian crime. “Until there is acceptance that [minorities] belong to society, there’s going to be an issue of pushback,” Thompson argued.

Thompson said that the issue of inclusion must be addressed by the church — how they embrace diversity and a sense of belonging. If churches are not making space for this, then they are complicit in perpetuating racism:

“It is not enough to say, ‘We have a diverse population within our church.’ The question has moved on to whether there is a sense of belonging for those individuals who have moved into the church.”

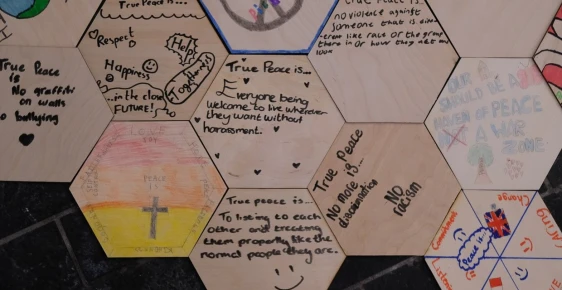

To underline this message, Thompson showed a video clip from The Giraffe and the Elephant, which is used to address diversity in the workplace. As the elephant struggles to use the workshop equipment designed for the giraffe’s characteristics of height and slimness, the giraffe suggests exercise and diet regimes to the elephant. Thompson said that this reveals a difference in cultural expectations (i.e. the elephant should change its character to suit the giraffe’s). A regular misunderstanding of adaptation, Thompson explained, was “Why should we change for others coming into our society?” Rather, he said, adaptation means flexibility. He described how most people are willing to give up superficial aspects — such as food, dress, and appliances — but preserve deeper attributes — such as language, privacy, and health and safety. Thompson challenged churches to examine cultural barriers in their church — structures, practices, and traditions — and ask which they need to keep exclusive for its survival, versus what they could be flexible about for the sake of inclusion.

The president of DCU, Professor Daire Keogh, made some brief remarks before the afternoon section. He said that the role of churches in Ireland has changed much in the past 25 years, and addressing identities on the island is the next step. Keogh described the history of DCU as a merger of three faith–based colleges into a secular one, to create an institution that was inclusive and pluralist, “more than secular — a space for all faiths and for none”. He added that DCU is home to two denominational centres (1) (2), “reflective of the kind of society we wish to create… Their presence has changed the university for the better.” Keogh recalled a remark by Archbishop John McDowell, who said that it was significant to observe the influence a church can have as the visitor, as a guest; the churches don’t need to be the host.

Called to be One book launch

Dr Ian Ellis described his new book, Called to be One, as “a continuation of history” of the ICC and IICM, and paid homages to two previous authors, Professor John Barkley and Rev. Michael Hurley. Ellis argued that ecumenism is mostly about people and personalities, and their interactions:

“Ecumenism is a spirit, a deeply motivated movement inspired by the Holy Spirit. This short book outlines how the Irish churches have journeyed together, and is my own attempt to capture how that work with the Spirit has motivated action and witness, as well as to set out the course of events and contributions of individuals throughout that journey.”

After Ellis spoke, Bishop Leahy recalled Ellis’s previous book, Vision of Reality, published in 1992, which placed an image of the church as a pilgrimage of people. “The pilgrimage has continued,” said Leahy.

Leahy highlighted Ellis’s reference to David Stevens in the book (p. 10), who as ICC General Secretary in its 1998 annual report said: “There are people and religious bodies who have traditionally been suspicious of, and even hostile to, ecumenical organisations but are increasingly prepared to reach out and cooperate. They will not ‘buy’ the old ecumenical ‘package’ but are prepared to link up with others outside their constituency, particularly on issues of common concern, e.g. peacemaking or combating sectarianism.” Ellis added that this could be seen “as a leaving behind of the whole concept of organic unity, the vision of one earthy communion of the faithful reflecting their true unity in Christ, while at the same time affirming an energised unity in cooperation in practical ways.”

Discussion group sessions

The delegates broke out into a set of sessions to discuss the role of churches in a variety of settings:

- Churches in a more diverse Ireland

- Churches in a more secular Ireland

- Churches in an unequal Ireland

- Churches, climate justice and care of creation

- Churches in an unreconciled Ireland

Feedback from the sessions was provided by Dr Brady and Professor McDonagh, moderated by Bishop Andrew Forster, when delegates returned for a final plenary session.

Brady’s summary included the value of looking back, acknowledging what has worked well, such as IICM’s prophetic work on sectarianism and violence. She asked what could be revisited here. Her further feedback was that delegates spoke about ensuring that actions need to work at a local, congregation level. Brady elaborated on this after a question from the audience: “Some local congregations want a blueprint, but one–size–fits–all won’t work. Actions need to be contextualised for the local community. IICM can provide peer support, information exchange, and a wider context.”

McDonagh’s feedback from his conversations was that working for the good and for God’s kingdom is not contradictory. Here he said it helps to think of being in a post–secular society — people may not go to church but still value religion in their lives. What matters is the organisation of process (actions), leading to the potential of an outcome, McDonagh said, also asking how do churches develop processes with other community–led initiatives as well as working with local government authorities.

Closing remarks

Bishop Forster summarised that the day, indeed this whole year, was one of “God calling us to listen and hear clearly… Sometimes we get caught up in the mumbles.”:

“I’m intrigued by the fact that in 1923, when the ICC first got up and going… partition just happened and the dying embers of the [Irish] civil war. The island was an absolute mess. The churches got together because they believed there was a better message. They believed in hope. They believed the gospel has something to offer in building peace in society. Fifty years later, in 1973, one of the worst years in the Northern Ireland ‘Troubles” — one of the worst years on this island — the Ballymascanlon talks happened. Because the churches came together and said [that] we have to offer something better to society.”

Forster said “wonderful things” have come out of these inter–church relationships. He gave one example from his local area, involving him and “the other bishop” in Derry/Londonderry, Bishop Donal McKeown (Catholic Church). For the past few years, during the week of prayer for Christian unity, together they have led a group of 60–70 Christians on a prayer walk around the city walls:

“The first time we did this, after we finished Donal turned to me and said, ‘Twenty years ago, this wouldn’t have happened. Ten years ago, it would have been in the news. Now, people expect it.’ It’s a really positive normalisation of good church relationships.”

But, Forster told the audience, relationships need to be handled delicately: “Being courageous doesn’t mean being careless.” For him, ultimately relationships are at the heart of what it means to be a Christian:

“A day like today, I don’t think there’s been too much mumbling… What’s been clearest for me is that the relationships that we have are really precious and beautiful… The challenge for us now is how we engage in a world, in a society, on an island, where there is a reticence and sometimes downright opposition from the church and what it would want to see… how we present ourselves, as followers of Jesus together, in a winsome way.”

“Republished with permission by Shared Future News.”